The below is just a very small snippet from our P2 course, which is taught by 2020 lecturer of the year nominee Nick Drape. A former practicing accountant and Kaplan Financial teacher, Nick currently lectures at the University of Liverpool where he specialises in management accounting and financial management. You can access the entire P2 course along with all of our other objective test and case study courses by purchasing our All Access membership.

1. Activity Based Costing: Some Context

Activity Based Costing or ABC, as it is often abbreviated to, is the method of assigning overhead costs to the products and services of a business. The overheads of the business are often referred to as indirect costs.

So, if we're talking about a manufacturing business, the indirect costs would be all the costs that aren't things like direct materials or direct labour hours. In other words, indirect costs are things that can't be specifically related to a product which has been produced.

Typical examples of this would be things like factory rent rates, supervisors' salaries, and also costs to do with things like procuring materials, setting up equipment etc. All of these things are indirect costs that can’t be directly related to products being produced.

ABC as an approach was initially put forward by the Consortium for Advanced Management International, and was then developed by academics in the 1970s and 1980s. Nowadays, ABC has widespread use. However, what some organisations have found is that even though there are theoretical benefits, it's a complex process, and ABC brings with it some problems.

However, what it absolutely does do is overcome the limitations of some of the more traditional approaches to deal with overheads such as absorption costing.

2. ABC - Definition

In defining ABC, first of all, what we would say is it is a more complex system of cost accounting than absorption costing. ABC gives us a much more detailed look at the manufacturing part of a business if we're talking about a manufacturing organisation.

And rather than thinking about things at a departmental level, which we often do with absorption costing, ABC offers a much more detailed approach of breaking a business down into its different activities.

With ABC, you assign costs to each activity in the production process, giving you a more complete picture of the actual costs.

Activity Based Costing is defined by CIMA as "...an approach to the costing and monitoring of activities, which involves tracing resource consumption and costing final outputs". (1)

So, basically, using resources, spending money and costing final outputs.

Source: Pexels

The classical scenario we see here is trying to work out the cost of producing products.

Now, when we're working out the cost of producing our products, or indeed, if we're a service organisation, providing our service, the direct costs incurred are always very, very easy to estimate while the overhead and operational costs are much more problematic.

The CIMA definition goes on to say "...resources are assigned to activities and activities to cost objects".

Cost objects are just something we're trying to work out the cost of e.g. a product or maybe a service that has been provided.

Continuing with CIMA's definition, it continues by saying "...the latter (i.e. cost objects) use cost drivers to attach activity cost outputs".

Now, what we've got here within this definition from CIMA are a couple of key terms that you'll come across time and time again when looking at the topic of Activity Based Costing.

The idea is that to actually offer a product or provide a service, there's a chain of activities that will take place for that to happen, and ABC is going to break the business down into these different activities.

Cost drivers

Let's focus on the term "cost drivers". A cost driver is a reason why in a particular part of the business, we essentially consume resources and therefore spend some money.

So, it's a reason why we're spending money. We're trying to identify for each activity, what it is that forces us to consume resources and therefore spend money as an organisation.

As we said, when it comes to Activity Based Costing (ABC), it's a more complex process than something such as absorption costing; however, that complexity brings with it, hopefully, much more accuracy.

That, however, depends on the business or organisation in consideration.

But in certain conditions, Activity Based Costing will absolutely provide much more accurate information when it comes to various elements of the business and in particular, one of the key reasons an organisation uses it is to work out the cost of what it provides.

Now, obviously, there are massive benefits to having much more accurate cost information. For example, if we're a business, we can set a more accurate price but also, as we will see, the ABC costing method gives us a lot of information to help us, hopefully in the long-term, manage and control our costs as well.

3. The Rationale for ABC

Source: Pexels

ABC is an approach which was traditionally designed for manufacturing businesses, but can be used in other organisations too. If we consider manufacturing businesses and how they've changed, the modern manufacturing environment is much different compared to the traditional manufacturing environment.

Let's have a look at a couple of the key reasons why that is the case.

First of all, in a modern manufacturing environment, general overhead costs tend to be a much bigger proportion of total production costs. In traditional manufacturing environments, the largest proportion of costs tended to be related to direct costs.

Taking the example of Ford, a company that produces motor vehicles, in the early 20th century the biggest costs they incurred in terms of production were things such as the direct materials (i.e. the actual tangible material items that went into the motor vehicles being produced), and then because they didn't have complex production lines with all the fancy machinery that we see these days, they actually had loads of direct labour.

Therefore, with the workers on the production line actually piecing together the different material parts of the vehicle, the vast majority of costs for Ford in that traditional factory environment were direct costs.

Overheads, while they still existed, were a relatively small proportion of what Ford's production costs were. As a result, the need to employ an approach such as ABC, which offers a really deep dive on the overheads, just wasn't required. A really detailed analysis of overheads would have been unjustifiable, because relative to the direct costs, they were quite inconsequential.

Activity Based Costing vs. Absorption costing

One of the assumptions with absorption costing was that overheads, by and large, tend to be fixed. When we talk about traditional overhead costs, we'll always talk about things like factory rent, business rates, and if we have some supervisors, they are paid salaries and so on and so forth.

Traditional costing methods allocate costs based on the number of units produced but do not take into account the resources used to produce them.

However, once again, it's the case that in a modern manufacturing environment, the production process is so complex, that we've got loads of overheads; but not all of them are fixed, certainly not over the medium to long term.

So, actually, if we have overheads that behave in different ways, we need to understand that behaviour, so we can hopefully work out an accurate cost.

And in the long-term, if we understand that certain overheads are influenced by certain things, it gives us the ability to hopefully control our costs in these areas as well.

So, the assumption that most production overheads are fixed simply doesn't apply as consistently in the modern manufacturing environment.

One of the limitations of absorption costing is the assumption that if an organisation produces a number of product lines, but a particular product line is produced in larger volumes, that product line should be assigned a greater share of the overhead expense burden.

Again, that was probably a safe assumption to make in traditional manufacturing businesses that typically made a small range of products.

In such a traditional environment maybe you had a primary product, which you were producing in massive volumes, which really placed a huge burden on the business in terms of production resources, and therefore, it was fair that it took a greater share of the overhead burden.

However, in modern manufacturing environments we typically see such diverse product ranges that they all place very, very different demands on the business.

Source: Pexels

If you think about modern electronics manufacturers like Apple, just think about all the different products they produce all the way from tiny MP3 players to really complex personal computers.

Nowadays, it just simply isn't the case that if something's produced in a larger volume, it necessarily places bigger demands on the business in every single area of the production process. In some cases that would not be true.

Traditional absorption costing just cannot deal with that complexity, whereas Activity Based Costing does a much better job with this.

Gone are the days when you had Ford motor vehicles producing one particular car. As Henry Ford famously said, “customers can have any car they want in any colour, as long as it's the Model T, and it's in black.”

Nowadays, modern manufacturing businesses have massive product ranges and there is huge complexity in terms of production processes for the different products within that range. And again, we, therefore, have that situation where different products put very, very different demands on the business.

Some products might require a huge number of parts, and so they place a massive burden on the business in terms of supply ordering. However, maybe they are then actually being produced in huge batches, so actually, when it comes to things like equipment setups and material movements, the product is less of a burden.

Because modern manufacturing sees the diverse product ranges placing very, very different demands on the business, Activity Based Costing with its more complex and detailed insights, is going to help us reflect that when we work out the overhead costs for these products.

4. The Mechanics of ABC

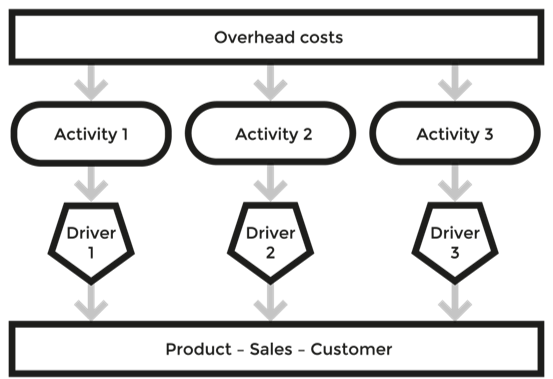

To represent the mechanics of ABC, we're going to use the simple diagram above. While ABC can be used in non-manufacturing environments as well, we'll stick with a manufacturing organisation for the purposes of this example.

What the business has to do here, if they are using an Activity Based Costing approach is, they need to:

- Estimate what the overall overhead costs of the business are going to be.

- Break the business down into the different activities that would have to take place in order for us to produce our products. So, you can see above that we've got three different activities but the reality is in the real world for an actual business, there could be anywhere between 50 and 100 different activities that would have to take place for the products to be produced.

Let's use some simple examples. A business might reflect on its activities and think: “Well if we're going to produce some products, the first thing we have got to do is buy some materials.” So activity one could be related to supply orders.

Now what we'd have to do is identify a cost driver for activity one.

An activity cost driver is the reason why we consume resources while we spend money on a particular area of our business.

So, a nice simple cost driver for activity one (supply ordering), might be the number of supply orders, because every time we have to place an order, while we have a procurement team who would be responsible for that, we're using resources. We're contacting the supplier by whatever means we use and therefore, that could be our cost driver.

So, activity one is supply ordering and cost driver one is the number of supply orders.

Now, if we can estimate what the overhead is and estimate how many supply orders we'll place in the period, we can then work out a cost per order. And then we can use that to charge overheads across our different product lines.

Activity two, if we leap forward in the production process, might be something like setting up our equipment.

We might think: “Well, every time we're going to produce a batch of products, we need to get the production machinery ready to produce that batch of products.” So, activity two might be production setups.

And again, it sounds a little bit boring, but it may well be the case that the appropriate cost driver is simply something like the number of setups.

If we’re going to make a batch of products, how many different bits of equipment do we need to set up to make that batch of products? And then once again, we'd be in that situation where we could say: “Here's the expected overhead cost related to that particular activity and here's a cost driver and we can work out a cost driver rate."

The final activity might be something along the lines of product inspections. Activity three is when we inspect our products to make sure they adhere to our quality standards.

So here, an activity cost driver might be the number of product inspections, and so we might have a policy within the business where we decide we are going to test 5% of the products produced, so we can work out what we think the inspection costs are going to be, how many inspections are going to take place, and then we can work out our cost per inspection. And so essentially, what we can do is we can use all of that information to charge our overheads.

To summarise:

1. overheads are allocated to activities.

2. then we identify cost drivers for each activity.

3. we work out our cost driver rates e.g. a cost per supply order, a cost per product inspection.

4. next, we use the cost driver rates to charge the costs of these different activities to our cost objects. Remember, a cost object is something that has been costed e.g. a product or a customer.

5. How ABC Works in Practice

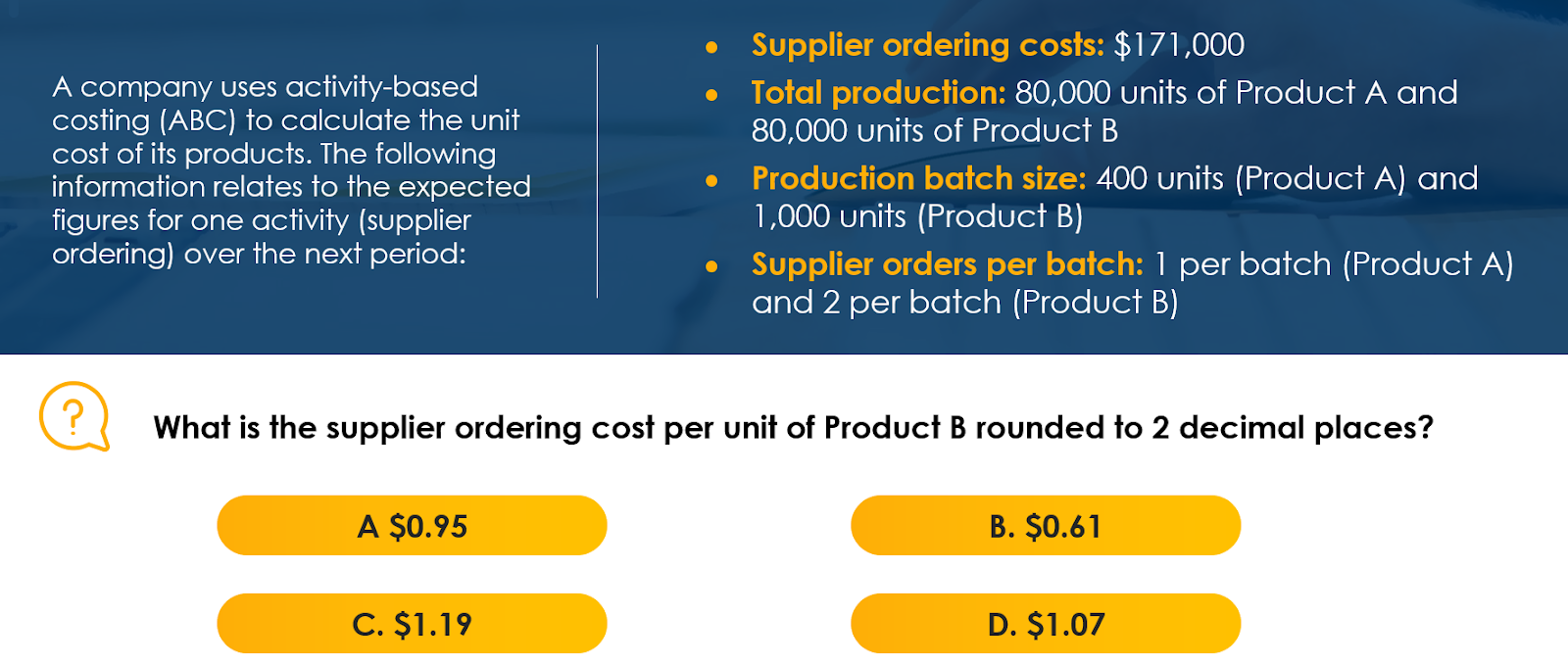

Let's take a look at a numerical example for Activity Based Costing.

In the question we're told that we have a company that uses the ABC system to calculate the unit cost of its products. We are given the expected figures for one particular activity, which is the supplier ordering costs over the next period. We're told that the supplier ordering costs are expected to be $171,000. We can also see that the company produces two different products - Product A and Product B, and we're expected to make 80,000 units of both products over the next period. We produce these products in different batch sizes.

So, Product A is produced in smaller batches of 400 units. That means every time we make a batch of Product A, we make 400 units each time. Product B is produced in larger batches of 1,000 units.

We're also told that we have to pay supplier orders every time we make a batch, and that makes sense, because if we're going to make a batch of products, we'd have to order materials. So, we have to place one supplier order for every batch of Product A produced, or maybe it's the case that actually we only need one type of material or component, so every time we make a batch of Product A, we order from that one supplier.

However, for Product B maybe it's a bit more complex in terms of materials or components that used, because we have to place two supplier orders per batch every time we produce a batch of Product B.

What we’re asked to work out is the supplier ordering cost per unit of Product B, and we've got a range of different options, A through to D.

We know where we want to get to but we've got to go through a number of steps in order to get there.

What we're trying to do is understand every time we make Product B, what is the cost for one unit of Product B in terms of supplier ordering costs? That's going be quite difficult to work out because we've got loads of supplier ordering going on, and we produce two different products. So, we've got to break it down step by step.

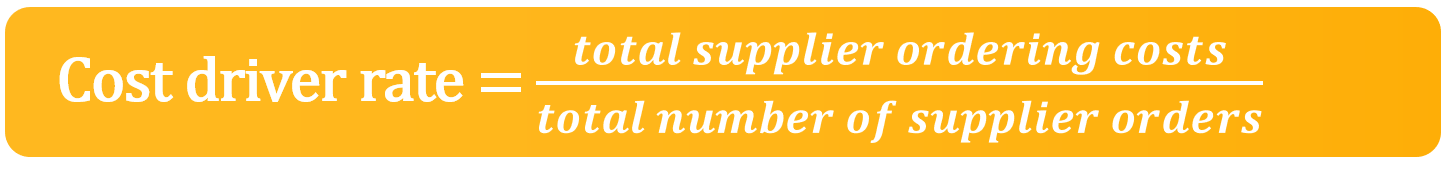

What we're looking to do is first of all work out what we'll call a cost driver rate. And once we've got that we can then work through some different steps and start working out the overall supplier ordering cost for a unit Product B.

To work out our cost driver rate, what we're going to want is total supplier ordering costs, which we know, but also, we then need to know our total number of supplier orders because what we want to work out is a cost for one order i.e. the cost driver rate.

In order to calculate the cost driver rate, we've got a few steps to go through first.

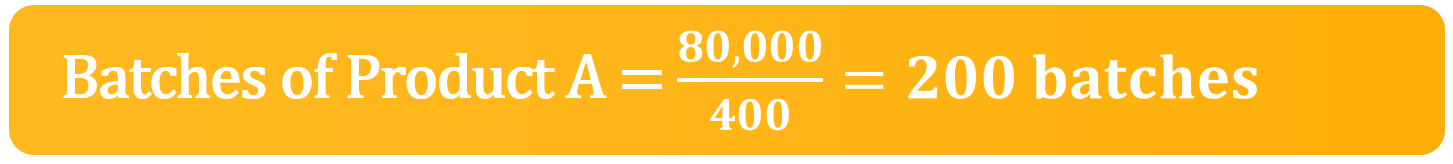

We are told the number of supplier orders per batch of each product. So, what's going to be useful first of all, is to work out how many batches of the product will be produced over the course of the period.

Product A is produced in batches of 400 units.

If we're going to make 80,000 units in the period as the question states, that means at 400 units per time, we're going to end up making 200 batches.

Product B, of course, is produced in larger batches. It’s produced in batches of 1,000 units.

So, if we're going to make 80,000 units in the period, with 1,000 units in each batch, it's nice and simple. That one is going to be 80 batches.

So in total, we've got 280 batches across two different product lines.

Now we're a little bit closer to working out our total number of supplier orders because we know how many orders we place for each batch of the two products, and that's our next step.

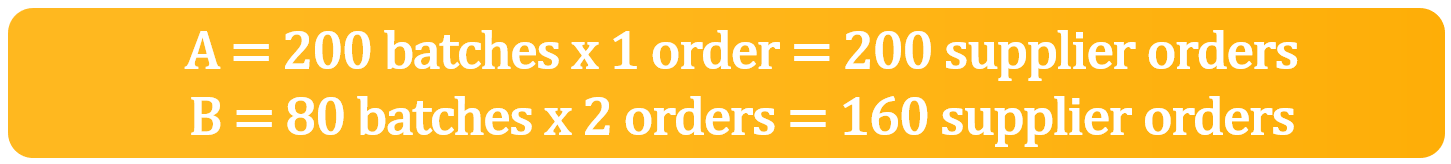

We are told that we place one supplier order for every batch of Product A produced. Well if we're going to make 200 batches of Product A, that's going to be a total of 200 supplier orders.

We place two supplier orders for every batch of Product B and we make 80 batches over the period according to the figures which are provided. So, at two orders per batch, that would be 160 supplier orders.

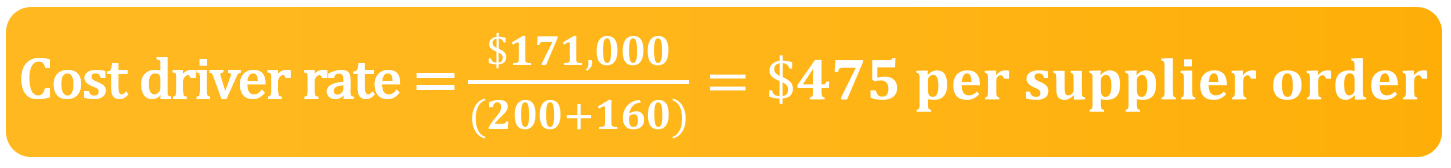

We can now work out our cost driver rate because we've got our total supplier ordering cost, which was given to us i.e. $171,000.

And now we know across the production of both product lines, we're going to make 360 supplier orders (200 for A + 160 for B).

Now, that works out at an average cost of $475 per supplier order. So, what we're really saying is on average it costs us $475 to place a supplier order.

We can now use this to charge our supplier ordering costs to our product lines.

Remember that in this example, what we want to work out is a cost for one unit of Product B, but we could do the same for Product A if we wanted to.

There are a couple of different ways you can go about this, but the easiest way is to first of all workout, based on the cost driver rate, what would be the total supplier ordering costs which we would charge for the production of all the Product Bs.

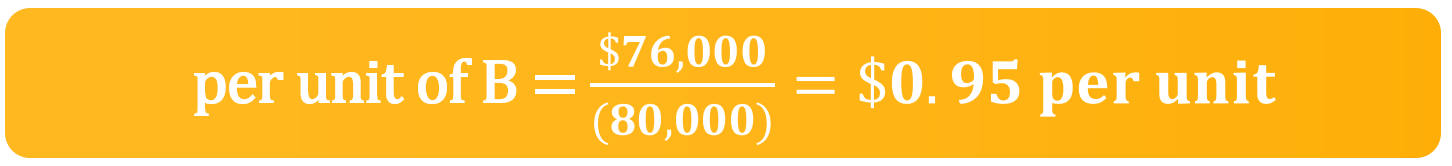

What we know is that in total we're going to have to place 160 supplier orders to make all the product Bs that will be produced, and the cost we just worked out is $475 per order.

So, that will give us a total supplier ordering cost allocated to product line B of $76,000.

Now, if we know the total supply ordering cost is $76,000, we can then finally answer the question: "what's it going to cost for one unit of Product B?”

We know in total, in the period, we're going to make 80,000 units.

So, we can take that $76,000 divided by the 80,000 units that we think are going to be produced and that will give us $0.95 per unit.

Therefore, the correct answer is A.

So, you can see that it's a step-by-step approach, particularly if you’re working down to a cost for one unit of a product.

You've got to think to yourself you need a cost driver rate, and then you're just working your way towards getting the figures which allow you to calculate that cost driver rate.

Additional Resources:

For access to all VIVA’s P1 Objective Test study materials, click here.

For access to all VIVA’s P2 Objective Test study materials, click here.

You might also want to read: Cost Behaviour and What are Relevant Costs?

%20(3).png)